Donald Stevens was born in Wellington, New Zealand.

He received his legal education at Victoria University of Wellington, New Zealand, graduating Bachelor of Laws in 1972, Master of Laws (with Honours) in 1976 and Doctor of Philosophy (in Jurisprudence) in 1987.

He was called to the Bar, at Wellington, on 2 March 1973 and commenced his legal career in 1975 as a staff solicitor at the Upper Hutt firm of solicitors, Beck & Co.

From 1978 until 1987 Dr Stevens was a principal in the Upper Hutt law firm of Basil-Jones & Stevens and from 1987 until 1990 he was the senior partner in the Wellington law firm Stevens Partners. In each firm he was the common law partner, responsible for criminal and civil litigation as well as family law work.

Since 1991 he has practiced at the independent Bar.

On 20 May 2002 the Governor-General of New Zealand appointed Dr Stevens a Queen’s Counsel and on 19 June 2002 he was called to the Inner Bar at a ceremony in the High Court at Wellington.

PhD graduate, 1987

For most of his career the primary focus of his practice has been criminal law. In this context Dr Stevens has developed an interest in human rights and civil rights issues. He has argued a number of Bill of Rights issues and wider rights issues both in the course of trials and before the Court of Appeal (including the Full Bench of that Court) as well as the Supreme Court. Some of these cases have focused on the principles relating to search and seizure (including when a search is unreasonable), the requirements for search warrant applications and the execution of warrants, the circumstances in which a search can be undertaken without a warrant; the right to trial without undue delay; fair trial rights; the right to privacy; and the standards to be observed when evidence is interpreted for an accused in a criminal trial.

Dr Stevens has also developed a secondary area of practice in torts, administrative law and international law, as well as professional discipline and regulatory law.

A substantial part of his practice has involved jury trial work with some appellate and opinion work as well as advisory work for government and the private sector. He defends a wide range of criminal charges and has often represented clients charged with the most serious categories of offences, including homicide, Class A drug offending and sexual offences.

Many of these cases have involved important legal and social issues. They have included voluntary euthanasia, battered woman syndrome, infanticide, child neglect and maltreatment, the treatment of drug addiction, drug rape, same gender sex in the Pacific, the rights of HIV+ people and sexual orientation issues.

Other cases have established precedents relating to the exclusion of unlawfully obtained evidence; the disclosure of the criminal convictions of witnesses; the undesirability of extended late night jury deliberations; the need for juries to deliberate in a room of adequate proportions; the circumstances in which oral evidence orders can be made in criminal proceedings; witness anonymity; the questioning of prospective jurors; and the principle that no adverse inference can be drawn in a criminal case when an accused person has exercised the right to silence.

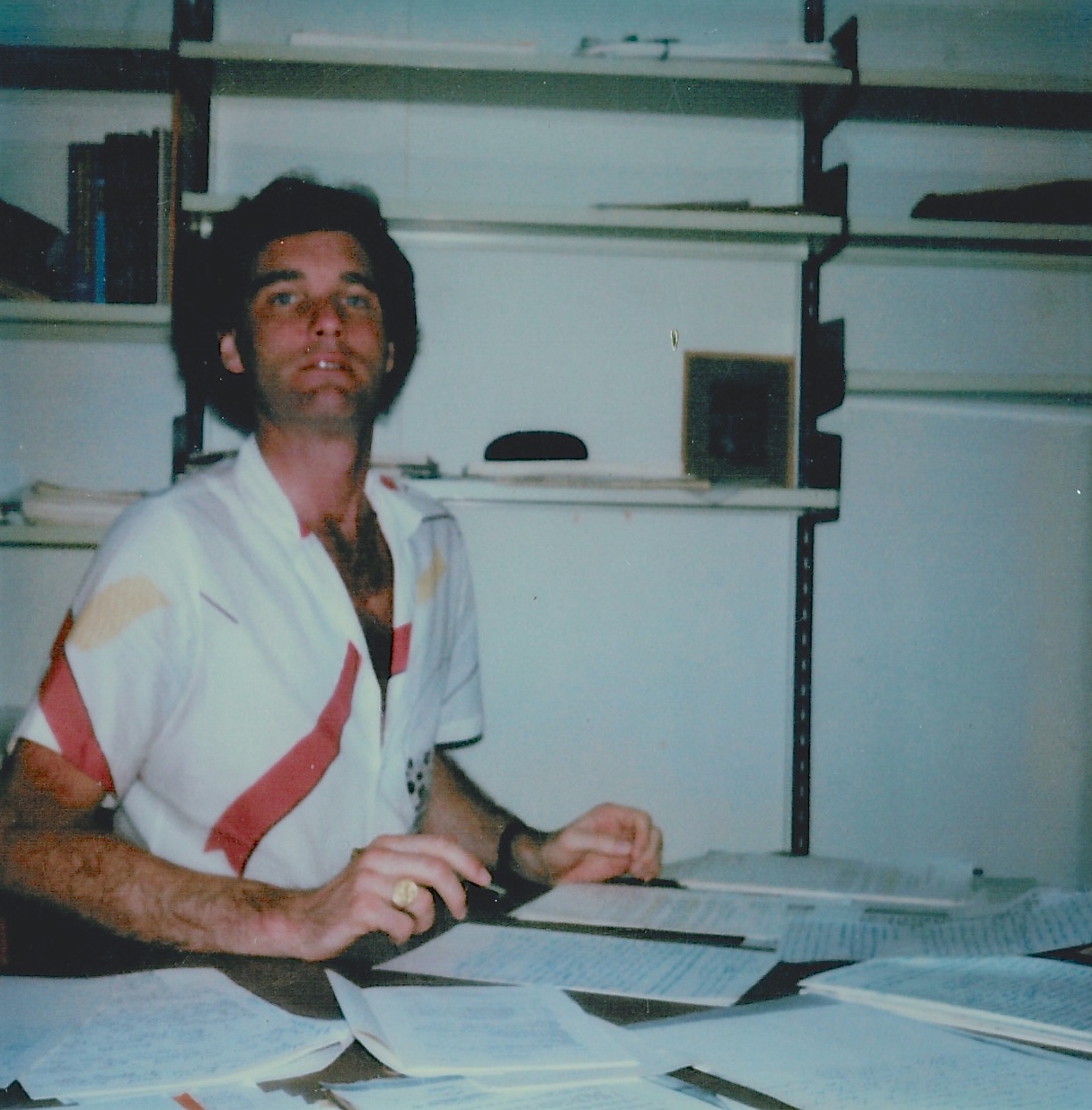

PhD student, c 1984

One case brought to an end the unsatisfactory position that had previously applied in a summary hearing of a defended criminal case in the District Court, where the defendant had no advance disclosure of the evidence to be adduced against him. It also introduced the regime under which the Crown, in a trial on indictment, made disclosure of material from the police file including statements made by witnesses to the police. This case established (using the Official Information Act 1982) the pre-trial disclosure regime that antedated by 20 years the Criminal Disclosure Act 2008.

Dr Stevens has successfully acted in criminal trials that have been factually and legally complex, including, in recent years, successfully defending a number of complicated prosecutions of health professionals and a medical supplier charged with fraud, each with multiple counts involving scores of factual issues and one involving allegations of fraud running to several million dollars.

He has been lead counsel for the defense in a number of murder trials – including several resulting in outright acquitals. These cases have sometimes involved over 200 Crown witnesses and up to 30,000 pages of disclosure material. They have also featured complex legal and factual issues, including expert evidence on forensic matters such as DNA and ballistics.

Dr Stevens has been counsel in a number of leading civil cases. Some of them have involved contemporary social issues such as the rape of men by other men, sexual abuse (one case involved a religious order), trade union rights, issues relating to the fabrication of evidence by police officers and one case involving legal issues concerning the recognition, in terms of international law, of revolutionary governments. He has acted in a number of cases where claims have been brought against the Crown in relation to the actions of police officers.

Aside from the practice of law, Dr Stevens has maintained an academic interest in the law. He has continued interests developed when undertaking research for dissertations presented for post-graduate degrees. He presented a Master’s thesis in 1974 entitled The Crown, the Governor-General and the Constitution, and a doctoral thesis in 1986 entitled The Licensing of Commercial Activity in New Zealand. Both led to the publication of articles in the New Zealand Law Journal as well as other publications. The New Zealand Economic Development Commission published part of the second thesis in 1988, as Occupational Licensing in New Zealand.

In 1983 Dr Stevens was the author of a substantial report on the licensing of kiwifruit exporters. This involved both administrative law and economic analyses.

Partner, Basil-Jones and Stevens, c 1980

Over forty of the cases he has argued have been reported in the official law reports in New Zealand.

Dr Stevens has on several occasions made submissions in his own name to New Zealand parliamentary select committees on proposed legislation that would impact on civil liberties. He made submissions on the legislation that allowed witness anonymity (in response to the decision of the Court of Appeal in a case in which he appeared as counsel) and made submissions on the legislation that allowed the detention of persons suspected of having controlled drugs concealed within their bodies. He also made submissions on legislation that authorizes orders for the removal of fortifications from premises, and subsequently argued, in the District Court and the High Court, the leading case involving rights issues decided under that legislation.

In 2005, he made submissions to a select committee in which he opposed legislation then proposed which would, amongst other things, curtail the right to a depositions hearing in a criminal case, make inroads into the rule of law providing protection against double jeopardy, restrict the right to trial by jury and reduce the number of challenges permitted in jury selection. In 2007 he made submissions on the Criminal Proceeds Recovery Bill.

Dr Stevens has lectured and spoken to community groups on civil rights and legal issues, tutored in constitutional law at Victoria University of Wellington, New Zealand, lectured at the Royal New Zealand Police College, presented papers at legal conferences and co-chaired with the Solicitor-General of India two sessions of an international conference in New Delhi, on issues relating to legal aid and its availability to visa victims and extradited persons as well as displaced persons.

Dr Stevens QC received at Government House, Funafuti, by His Excellency the Acting Governor-General of Tuvalu, The Reverend Tofiga Falani MBE.

(August 2017)

Recently Dr Stevens has, as a sequel to the research he undertook into the office of governor-general when writing his master's thesis (and as a continuation of his interest in constitutional law), commenced research into the manner in which governors-general are selected in Commonwealth realms. The research is focusing in particular on those countries where the governor-general is elected by an electoral college. The issue of a governor-general's security of tenure – or the lack of it – is being considered. So also is the question of whether the standing of the office of governor-general should be reinforced by it being accorded full viceroy status, effectively making the governor-general head of state.